Managing a Miniature Menace

go.ncsu.edu/readext?707597

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲A practical guide to spotted wing drosophila (and blueberry maggot) management in Piedmont blueberries

Background

With the Piedmont blueberry season ramping up, it’s time to be thinking about managing spotted wing drosophila (SWD), an important pest of blueberries and other soft-skinned fruits. Blueberry growers in Southeastern NC have reported SWD larvae in fruit this year. SWD populations tend to start out small and build rapidly around the beginning of July. It is not possible to eliminate these insect pests from fields, but growers need to take steps to keep fly populations and infestation, i.e. egg laying in fruit, in check. Monitoring and cultural practices are ready tools for the small-scale blueberry grower to sustainably manage SWD this season and beyond.

Background and Life-Cycle

The spotted-wing drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) is an invasive fruit fly from Asia. It is an extremely adaptable species and now ranges from Canada to Georgia. It is the main pest of US small fruit crops, causing damage estimated at over $800,000 dollars/year to growers. They attack soft-skinned fruit crops, including blueberries, strawberries, and grapes, and are most destructive to raspberries and blackberries in North Carolina. SWD are a fruit specialist, but their diet is very diverse including over 130 known crop and non-crop hosts. The female adult flies lay eggs under the fruit skin, eggs hatch, and tiny larvae, or maggots, hatch and feed inside ripening fruit. This causes severe damage and makes fruit unmarketable. Because SWD have multiple (up to 16) generations per year, and a short life cycle, infestation can build quickly and thus needs to be detected early.

Undamaged fruit or after 1 week of SWD infestation. Photo by Vaughn Walton, Asplen et al 2015.

Identification

Managing insect pests begins with accurate identification and knowing the lifecycle of the pest. SWD are distinguished from other drosophila species by spots on the wings of adult male flies, from which it is named. Females have a distinctive, serrated ovipositor, or egg-laying device, used to puncture fruit skin.

Female SWD are identified by their relatively large, saw-like ovipositor. Image © Matt Bertone, Inset Hannah Burrack

SWD larvae looks superficially similar to the blueberry maggot (Rhagoletis mendax), a native pest in blueberries. Adult blueberry maggot flies have three black bands on their wings, and adults and larvae are larger than SWD.

Larva of “true” fruit flies (Tephritids), which include the blueberry maggot fly, and larva of Drosophilids which include SWD.

The distinguishing feature is not larva size but shape. Blueberry maggot larvae are “carrot-shaped” pointed on one end and blunt on the other, whereas SWD larvae are pointed on both ends.

Blueberry maggot is more of an issue in the Piedmont vs. Southeast growing regions. Infestation can be far more severe than SWD if left unchecked. However, insecticides are quite effective, and can essentially eradicate blueberry maggot populations from the field. In organically managed operations or the many small, u-pick operations that don’t spray, blueberry maggot remains a real management challenge. These growers need to have this pest on their radar, and consider using cultural controls if not applying insecticides.

Monitoring

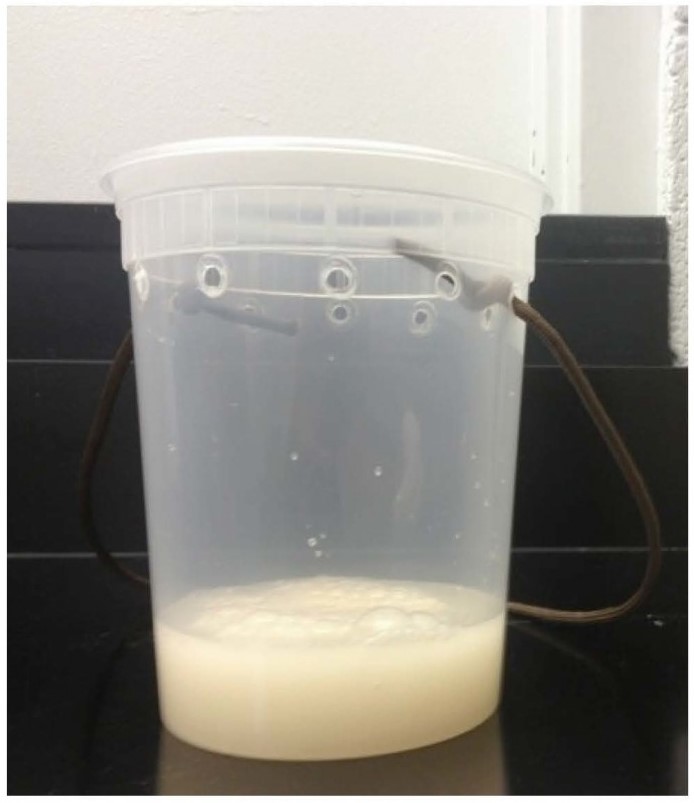

Trapping is a way for growers to monitor the number of flies in the field to gauge the risk of crop infestation. Traps tell you whether or not you have flies in the field, but not whether there is infestation in fruit. Baited “yeast and sugar” traps are effective at catching adult SWD, and can be homemade at low cost. Commercial lures and traps* are also available for SWD. These are just as effective as homemade lures.

SWD Monitoring Trap. University of Georgia, 2014. UGA Blueberry Blog

Yellow sticky traps are preferred for trapping blueberry maggot. The number of traps depends on the size of your planting, but a minimum of 3 is recommended. For best capture, hang traps in the upper third and a shaded area of large bushes. Check traps at least weekly.

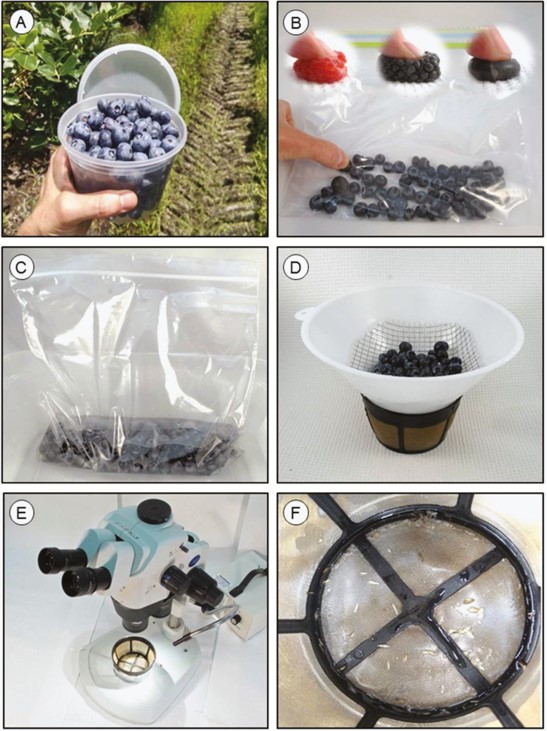

Fruit must be sampled for larvae to tell if there is infestation. Sample blueberries using a salt extraction test (figure 1). Take a 1 cup sample of fruit, gently crush in a salt solution of 1 Tablespoon salt for 1 cup water, let set for 1 hour, and filter it through a reusable coffee filter. Count the larvae that have exited that time period. Identification can be confirmed by your local extension agent.

Information on the presence and level of fruit infestation can be used to target insecticide sprays, identify an unmarketable crop, or verify that no infestation exists.There is zero tolerance for a single SWD larva in commercially marketed fruit.

Management

SWD are challenging to manage because populations can build rapidly during the growing season. Numerous insecticides are effective at managing SWD. Broad-spectrum insecticide such as phosmet, malathion and pyrethroids, provide control with frequent application. Many blueberry operations in the piedmont are organic or use minimal pesticides, and must turn to cultural practices. Below are recommended practices that provide SWD control:

- Begin monitoring early following a mild winter. Prolonged cold temperatures are needed to kill overwintering flies, and more flies survive in a mild winter. After a mild winter, flies can show up earlier in the field, and growers need to get out monitoring traps early.

- Destroy alternative food and habitat near field edges. It is impossible to eliminate all non-crop SWD food sources which includes weeds, flowers, fungi, and manure. But removing wild fruit, fruit waste, and compost is an attainable and effective way to control flies in-season and overwintering sites.

- Harvest as frequently as possible and collect dropped fruit. Sanitation removes SWD larvae that are most often found in damaged or overripe fruit.

- Hold fruit in cold storage. Temperatures <34°F for 3 days or longer will kill at least some SWD larvae and keep eggs from hatching. Post harvest chilling can significantly reduce infested fruit.

- Prune regularly (maybe?). New research suggests that pruning reduces SWD pressure by increasing canopy temperature. SWD do not tolerate high temperatures >90°F, and tend to lay eggs in the central portion of the canopy where it is cooler and more shaded. Prune lets more light into the central canopy and makes it less hospitable for SWD.

Exclusion netting is another non-chemical control and can be highly effective at preventing infestation. Netting is expensive, can be damaged in storms and must be removed to allow for pollination, a cumbersome task. Ongoing research is looking at 1) time of day and areas of the field and canopy that infestation most occurs, and 2) factors that affect overwintering so we can better predict high and low risk seasons.

Fig. 1. Follow these steps to sample fruit for SWD.

*Supplier links are provided for informational purposes and not intended to endorse any particular supplier over another.